The Origin Story

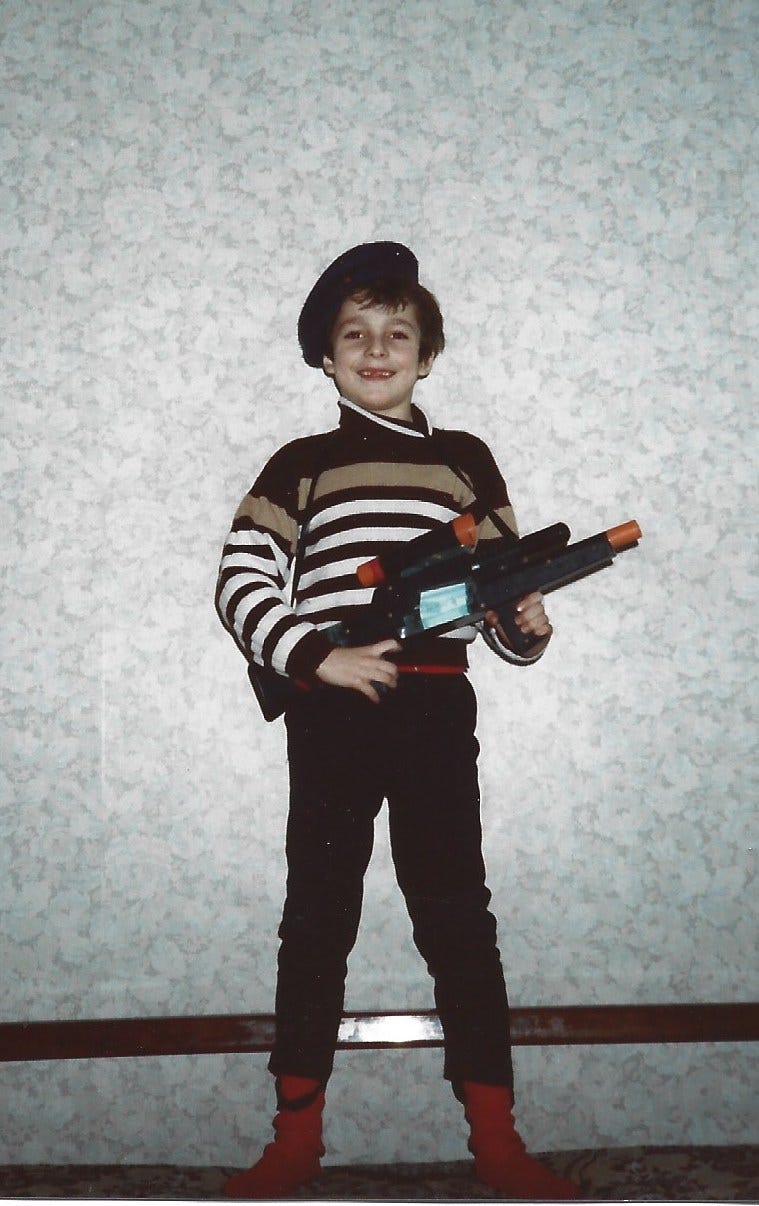

My career in international relations began when I dressed up as Saddam Hussein for talent day at kindergarten. Black beret, high boots, and a toy rifle in place of a real AK — aside from a few missing baby teeth, you practically couldn’t tell the ruler of Baghdad and me apart. It was during the last days of the Soviet Union, and everything was in disarray: Gorbachev was despised by hardcore nationalists for letting the Eastern Bloc dissolve, communism saw unprecedented — and unpunished — criticism from within, and food, as it often happened in Russia, was somewhat rationed. There was a limitless supply of wakame seaweed, but you had to have a voucher if you wanted some bread. So it was only normal that on talent day, Petya came as a penguin, Olya was a sunflower, and Andrei dressed up as a murderous dictator. At least, that’s what the counselor told my mom.

My foray into Russian domestic politics happened a year later when I was eight. One day in August, I saw my mom glued to the radio. She said there’d been a coup and that Gorbachev was deposed. I was past my Saddam stage and into all things dinosaurs, including the gerontocratic communist nomenklatura. I asked mom if the Soviet minister Yanayev was behind the coup. She said that she didn’t know. Later, mom got a call from her friend in Moscow, who told her that Yanaev had tried to seize power. Even at eight, I knew he didn't have what it takes to rule Russia; I was right about that, too.

I could always see through the various shades of evil permeating my country of birth. There is no specific method to my analysis: I assume the worst that could happen and single out the ones capable of making it happen. I didn’t even have to go to Harvard for that; all I had to do was down a few bottles of Cristal with some of the most profoundly immoral people the motherland had to offer. I had to listen to their dreams, needs, and delusions. I was always fascinated by evil, but inevitably, it came with a price. Rubbing shoulders with oligarchs, politicians, and propagandists made me cynical, and my moral compass is faulty at best. I was never part of their decision-making process, of course, never held any post or even had government money in my pocket. I tried to compensate. I went to protests and helped Pussy Riot. I donated to political prisoners and independent Russian media. Still, I can’t help but think that I could have done more to stop the people whose deranged ideas and ethics ravaged Ukraine — the land of my parents — and caused the deaths of tens of thousands of innocent people.

I’ve written about Putin and all things Russia for The Guardian, Air Mail, Village Voice, and many other publications, but Breaking Russia is different. Not your dry, somber newsletter from Russia-watchers with three PhDs and zero social skills, it’s a human, often humorous take on the gossip, political commentary, and breaking news coming from the worst place on earth. You’ll laugh (in horror) at the anecdotes from the Russian elite, and meet some of the brave women and men who fled one of the most brutal police states in modern history only to fight it from abroad.

Breaking Russia isn’t just a commentary on the latest from the dark Empire; it’s my attempt to break that empire inside me. Unlike Russian politics, I have no idea where this journey will take me. But I know two things: you’ll love it if you come along, and — I promise — I won’t dress as Saddam.